Only thanks to the innovations made in the nineteenth century did the olive production of southern Latium open to the European market, from being a deficit, the Roman trade balance became active compared to olive oil.

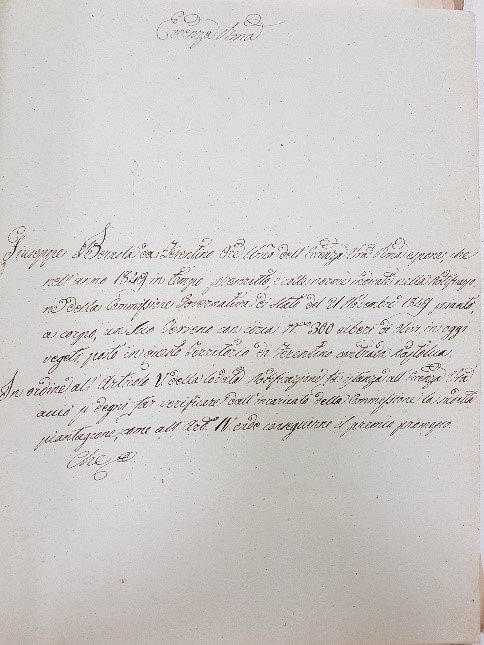

On April 21, 1788, the Pope issued a Moto Proprio with which he granted a prize of one Paul for each olive planted, confirmed in 1801 by Pius VII in the motu proprio "The most cultured" and in 1830 by Pius VIII. The cultivation of the olive tree had a great increase (200,000 plants were planted throughout the papal state).

Pope Pius VII immediately imposed radical and unprecedented measures to overcome the general economic difficulties, also due to the devastation of the French invasion: with the motu proprio he liberalized trade and the price of products within the State.

The Pontiff wanted to bring to the attention of all citizens and to that of "Reproducers" or farmers, the situation of the public Annona and the justified fear that foodstuffs coming from abroad or from other provinces of the State would not be sufficient to cover the needs of the population of the capital.

In fact, due to some restrictive trade provisions issued by the previous popes, the "Reproducers" were obliged to sell oil, wheat, corn, and other similar products to the public Annona at such a low price that it often did not cover the expenses of production.

Pius VII, therefore, to remove the spectre of famine that always loomed over the State of the Church, decided to abolish any edict that had obliged farmers to sell their products to the public Annona, granting them the right to sell wheat and similar products in any place of the State, with ample power to negotiate the price, provided that said products "... are not transported out of the State, on which we want, that the current prohibitions continue to be in full force ..."

With the Motu Proprio of November 4, 1801, penalties were also established to be applied against owners or tenants who attempted to illegally export the products “in all cases of fraudulent extraction of Grains, Maize, Flours, Legumes, and any other sort of Grains, and of Fodder, as well as of Beasts, Salted Meats, Oil, Cheeses, and any other kind of Grascia, in addition to the loss of the Genus, no less than the wagons, Attracts, Beasts, Boats, on which they were transported , and although these were not the property of the Fraudanti, the patrons will be subjected each time to a strong fine at will, but not less than three hundred scudi, and they will be irremediably, and without hope of grace, condemned for the first offense to the Jail for Ten years and in case of recidivism to perpetual jail”.

Pius VII, therefore, to remove the spectre of famine that always loomed over the State of the Church, decided to abolish any edict that had obliged farmers to sell their products to the public Annona, granting them the right to sell wheat and similar products in any place of the State, with ample power to negotiate the price, provided that said products "... are not transported out of the State, on which we want, that the current prohibitions continue to be in full force ..."

With the Motu Proprio of November 4, 1801, penalties were also established to be applied against owners or tenants who attempted to illegally export the products “in all cases of fraudulent extraction of Grains, Maize, Flours, Legumes, and any other sort of Grains, and of Fodder, as well as of Beasts, Salted Meats, Oil, Cheeses, and any other kind of Grascia, in addition to the loss of the Genus, no less than the wagons, Attracts, Beasts, Boats, on which they were transported , and although these were not the property of the Fraudanti, the patrons will be subjected each time to a strong fine at will, but not less than three hundred scudi, and they will be irremediably, and without hope of grace, condemned for the first offense to the Jail for Ten years and in case of recidivism to perpetual jail”.

Notifications relating to the prohibition of grazing in olive-growing areas and reporting of the theft of olives

The Pope, wishing that the norm of compulsory cultivation of the countryside be applied and that cultivation prevail over pasture, brought back into force all the prescriptions issued for this purpose: he did not neglect to add other penalties against those landowners who had not followed the previous laws. and, in the certainty that so many territories suitable for cultivation were abandoned, both in the Roman and Pontine countryside and in the territories of Montalto, Corneto, Toscanella and in the State of Castro, he ordered that a new tax be imposed on the owners of uncultivated land.

The uncultivated lands had to be burdened, in addition to the Dativa Reale, by an annual surcharge of four paoli per rubbio, furthermore anyone who had worked lands, removing them from grazing, had to receive a premium of eight paoli per rubbio provided that, by the month of April, had presented the documents for the request for the premium with the certification of the cultivated land.

Understanding that all the measures previously adopted would not have been sufficient to raise the conditions of agriculture, the Pontiff decided with the "Motu Proprio" of September 15, 1802 to undertake the reclamation of the countryside and the reduction of large estates in the Papal States, and deeming it urgent to drain the swamps to eliminate the danger of malaria and understanding that this work would require large amounts of money, ensuring that the Apostolic Chamber would have to contribute to the expense.

In the same "Motu Proprio, cash prizes were established for the construction of farmhouses, and the Pontiff also wanted the colonists, if they had requested them, to be able to obtain from the hospital of S. Spirito a foundling or an orphan for each family, to educate and instruct them in the agricultural art.

On 14 June 1800 Napoleon defeated the army of the Second Coalition in Marengo and re-founded the Cisalpine Republic. The legations of Bologna, Ferrara and Romagna were again taken away from the Holy See. In 1805 they were incorporated into the new-born Kingdom of Italy. The French organized the administration in bureaux under the control of the occupants: public documents began to be issued in the two languages Italian and French. At this juncture, new emergency measures were approved to achieve a balanced state budget.

In November 1807 the provinces of Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Spoleto were again occupied. Pius VII officially protested, but it was not enough: in April 1808 the occupied provinces were annexed to the Kingdom of Italy. Between January and February 1809 Latium and Umbria were occupied north of Spoleto. On February 2, the French entered Rome and on May 17 Napoleon decreed the abolition of temporal power, annexing Umbria and Latium to the French Empire. Pius VII was arrested (6 July 1809) and deported across the Alps, his imprisonment in France lasted until 1814.

The French administration between 1811 and 1812, in addition to reconfirming the papal state's choices in the olive sector, made further efforts to raise awareness among farmers but also economic ones with the allocation of 12,000 francs to encourage olive cultivation. It is worth remembering Camille Philippe Casimir Marcellin, Count de Tournon-Simiane (born June 23, 1778, died June 18, 1833) was a high-ranking French official and noble of France, Prefect of the Department of Rome of the Napoleonic Empire from July 15, 1809 to January 24, 1814 and set out to understand and describe the economic and social reality of the latter and in particular collected statistical, topographical, administrative and economic data. In fact, we know that the results of the important intervention of the French administration did not take long to make themselves felt that thanks to the new plants cultivated in those years and thanks, above all, to the progressive of the plantations made in the previous ones. The olive tree area in Latium reached, in 1813, 27,000 hectares with an oil production of 3 million kilograms. The situation improved so much that at the time there was talk of a prodigy.

In the "arrondissement" of Velletri the area of Latium with the greatest cultivation was that of the southern slope and the total number of olive trees was around 2,355,000-2,555,000.

Of these 1,355,000 were concentrated in 5 municipalities:

| Sezze | 700.000 |

| Cori | 400.000 |

| Piperno | 100.000 |

| Sonnino | 100.000 |

| Terracina | 55.000 |

In the Sonnino area a well-developed plant in good years yielded about a quarter of a rubbia of olives and an average of 5 sheets of oil (1 rubbio = 213.3 kg, 1 sheet = 0.513 liters), half of the oil was consumed on site the rest generally flowed to Rome.

The Roman trade balance became active for olive oil, fuelling a interesting export.

After the fall of Napoleon, in the battle of Leipzig, the territories occupied by the French were returned to the Holy See on January 24, 1814 and Pius VII returned in the fullness of his powers. He continued the already started economic and agrarian reform.

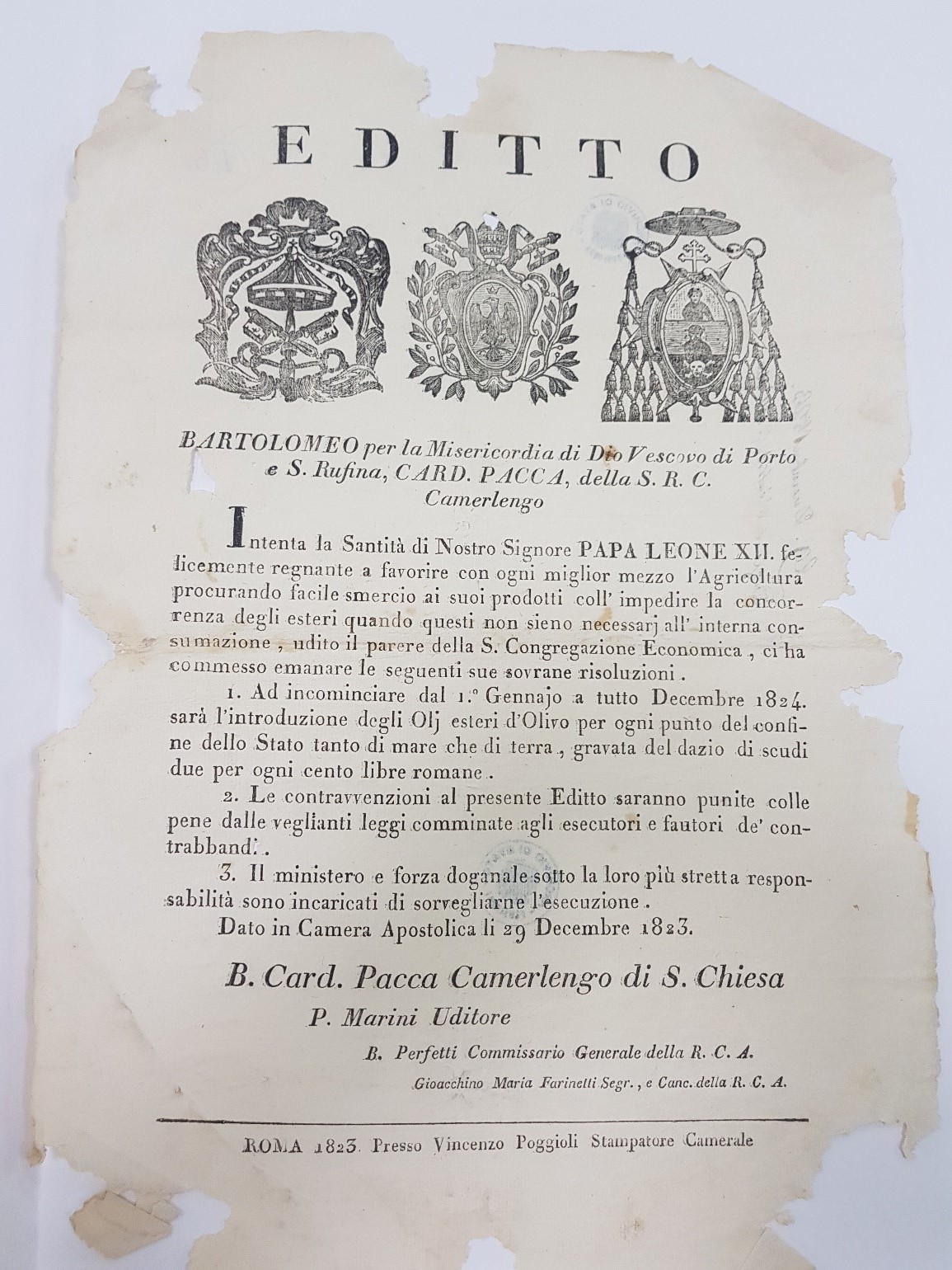

On 28 September 1823 Pope Leo XII ascends to the papal throne, his economic policy was characterized by its conservative character. While Europe opens to the liberalization of trade, he burdened foreign products with very high papal duties. His attention turned particularly to the production and trade of oil as evidenced by the motu proprio issued in 1826.

Olive growing in the 19th century

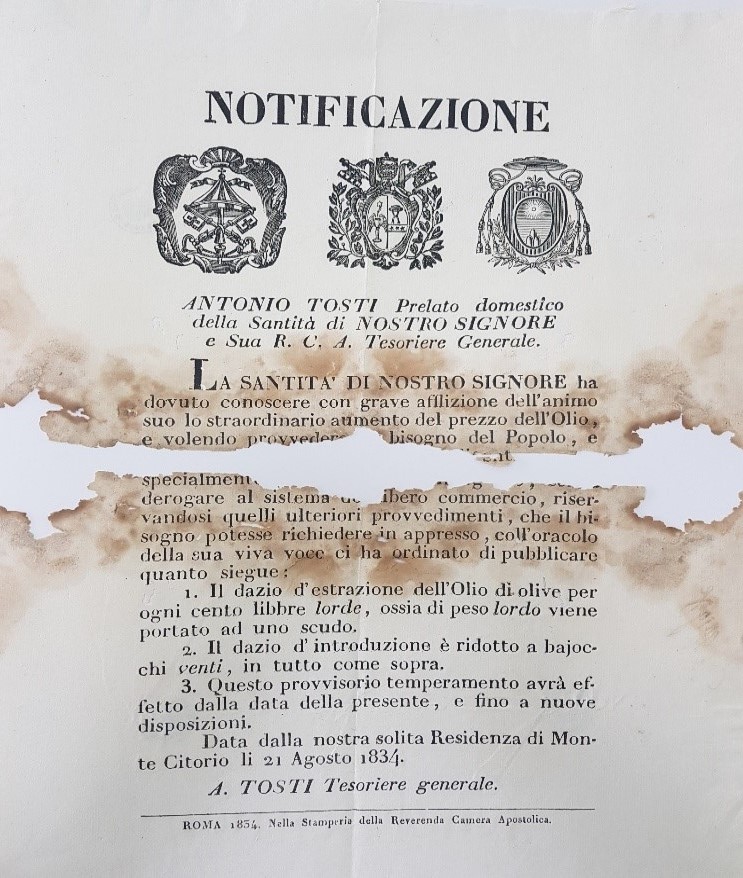

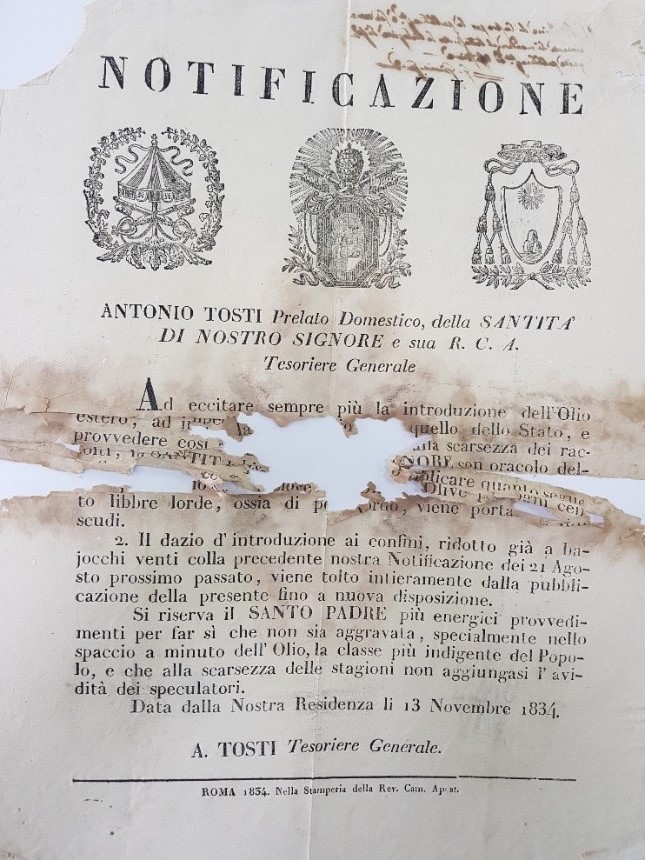

In 1834 all the important papal reforms were confirmed. And, that led to a large increase in olive growing in southern Latium. In 1838 the area devoted to specialized olive cultivation in Latium went from 80,000 hectares to 84,000, so much so that in the notes of the time it is certified that “in the Delegation of Frosinone the mountains of Vallecorsa, Piperno, Sonnino, Maenza, Bauco, Veroli and Alatri stand out for the abundant and excellent oil that is collected in them, and of which there was then an interesting sale with Rome” and that in particular “the mountainous region of the territory of Bauco looks north and east, and is crowned with abundant and luxuriant olive trees, from which excellent quality oil is collected which is transported for large loads to many parts of Italy”

In fact, the Frosinone’s territory took on the characteristics that we can see today. The prevailing presence of terraces mostly designed by elaborate dry stone walls that testimony of a conscious use of the territory. All this allowed the cultivation of even a single olive tree in one soil.

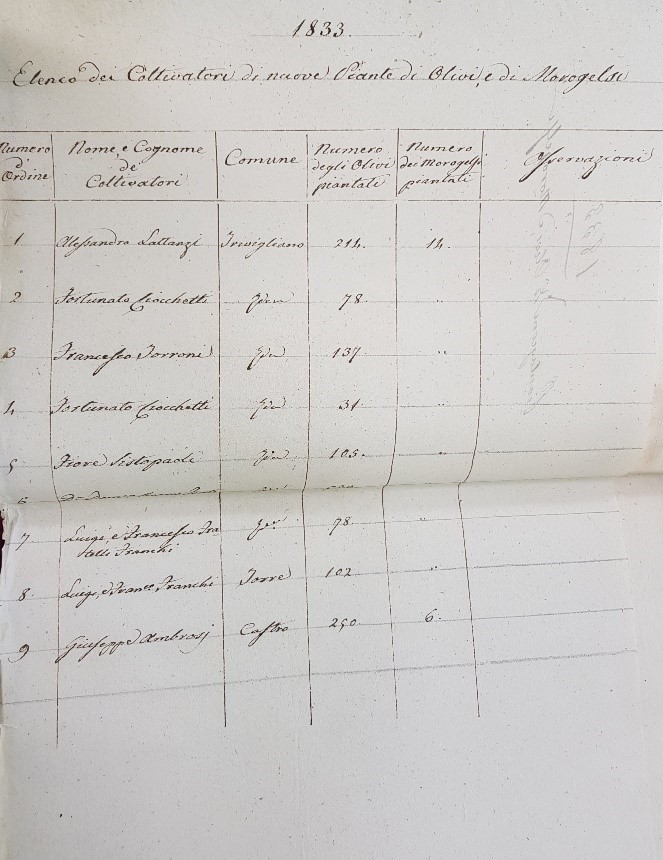

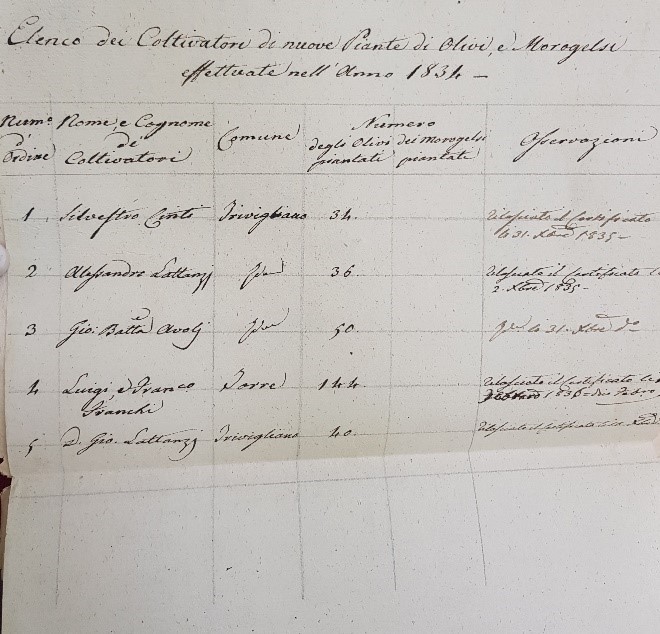

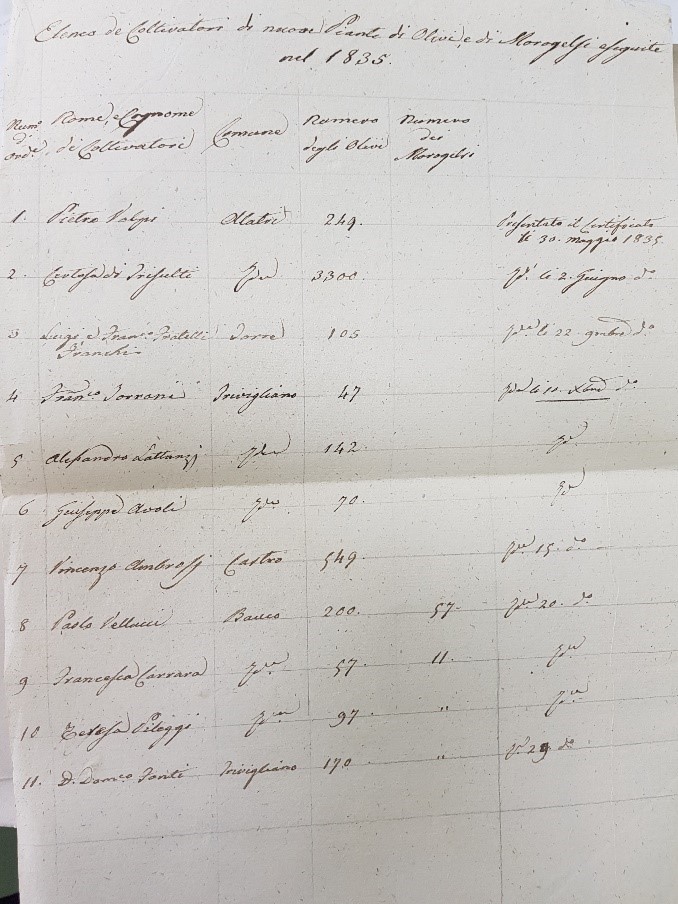

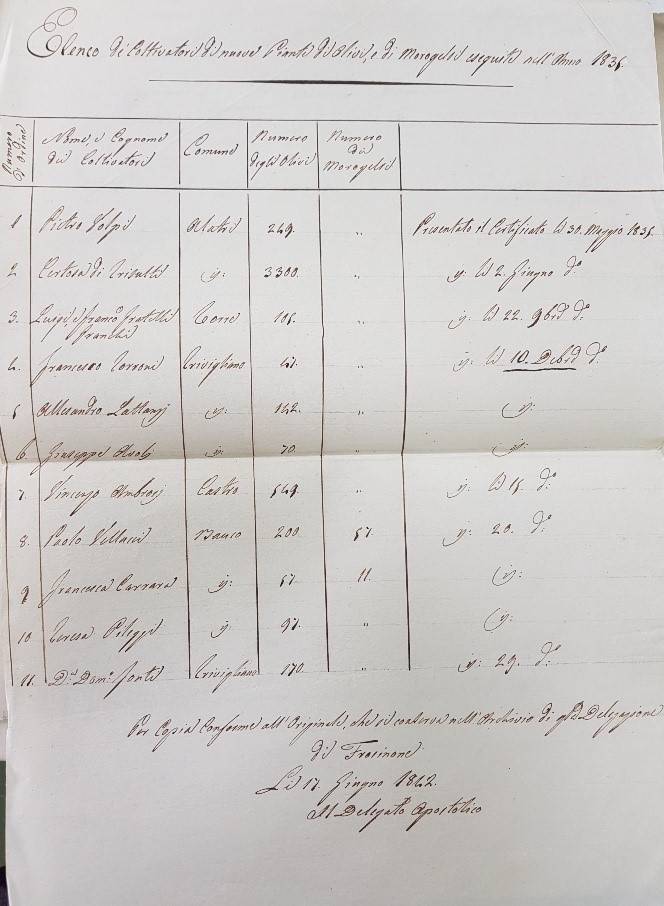

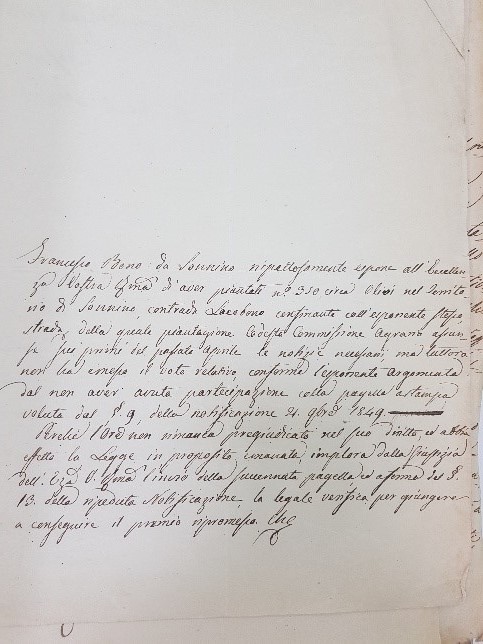

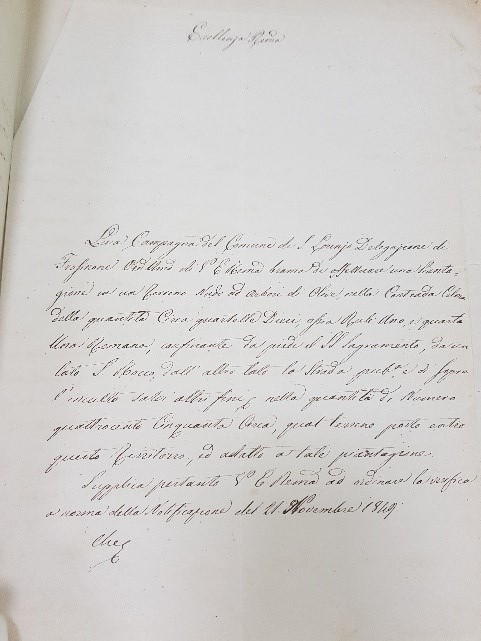

In the records of the apostolic delegation of Frosinone there is a memory of the important olive growing that took place in the various municipalities. Belonging to it, this was mainly thanks to the prizes introduced starting from the pontificate of Pope Pius VI and confirmed by his successors.

Further actions to support olive growing were initiated by the papal state by granting further prizes which resulted in the annual planting of 50,000 olive trees between 1856 and 1858. (Attachment 4).

On March 15, 1877, the famous Agrarian Inquiry was launched during the government chaired by Agostino Depretis, exponent of the historical Left. The aim was to verify the economic and social conditions of the Italian countryside and the state of national agriculture.

Jacini, president of the commission of inquiry set up for this purpose from 1881 to 1886, published a voluminous report in 1884, still known today as the Jacini inquiry.

The investigation, promoted by the Chamber of Deputies on 15 March 1877, shows that the olive tree was cultivated in 179 municipalities out of 227 in Latium territory. And, that the olive groves extended over an area of 41,667 hectares, among the places where the presence of olive trees was more extensive, with Sonnino standing out.

Thanks to the reforms, carried out by the Papal State and continued by the French administration, agriculture was greatly favoured in the border areas with the Kingdom of Naples. In fact, the contacts, and exchanges between the two states were facilitated. And, the area of Sonnino, Itri and Gaeta were particularly characterized by the presence of the olive tree.

Olive growing is so deeply linked to the social fabric that it has conditioned the development of the territory for centuries. Consequently, the life of the populations that have followed over time is, almost exclusively, based on olive production.

In conclusion, we can affirm that, today, the Olive tree is certainly the most cultivated tree species in the province of Frosinone and in the Pontine hills, this is mainly due to the temperate climate, excellent for the development of this crop and to the spelling of the territory.

Only thanks to the innovations made in the nineteenth century the olive production of southern Latium opened up to the World. And, the oil, that we could emphatically define the Oil of the Popes, as well as the plantations that today characterize the orogeny of the territory, are absolutely the fruit of the great investments of the Papal State.